Imagine the unthinkable: you stumble upon something deeply wrong, a scene that screams "crime." Your heart pounds, your mind races. In those terrifying first moments, a clock starts ticking, setting off a complex, meticulous process known as The Crime Scene & Initial Discovery. This isn't just about finding clues; it's about safeguarding the very fabric of truth, preventing its unraveling before the story can even begin to be told.

From the urgent call to 911 to the first uniformed officer stepping onto hallowed ground, every action taken, or not taken, can dramatically impact the outcome of an investigation. It's a high-stakes ballet between urgency and precision, where the initial actions of first responders are arguably the most critical. They're not just securing a location; they're preserving a fragile narrative, ensuring that every piece of physical evidence — no matter how small — can someday speak its truth in a court of law.

At a Glance: What Happens When Crime Strikes

- First Responders are Key: The very first officers on scene have a dual mission: provide emergency aid and secure the area to prevent contamination.

- The Scene is Sacred: Once secured, the crime scene becomes a controlled environment, a "frozen moment in time" for investigators.

- Documentation is Paramount: Every detail is photographed, noted, and sketched to create a permanent record of the scene's original state.

- Evidence is Fragile: From fingerprints to DNA, physical evidence is easily destroyed or contaminated, demanding meticulous collection and preservation.

- Chain of Custody: A rigorous paper trail ensures the integrity of evidence from the scene to the courtroom.

- Team Effort: A diverse group of professionals, from forensic scientists to detectives, collaborates to piece together the puzzle.

The Critical First Moments: Why Initial Discovery Matters Most

When a crime occurs, the immediate aftermath is a whirlwind of chaos and uncertainty. Whether it’s a sudden violent act or the discovery of something suspicious, the clock starts ticking the moment a crime is discovered. This initial phase, often handled by patrol officers – our first responders – is not merely about showing up; it's about making split-second decisions that can make or break an entire investigation.

Their primary objectives are immediate and vital:

- Rendering Aid: The absolute first priority is to assist any victims and ensure their safety. This might mean calling for medical help, performing CPR, or offering immediate protection from further harm. Life-saving measures always take precedence over evidence collection, but even here, trained officers learn to observe and note while acting.

- Securing the Scene: This is where the foundation of the entire investigation is laid. Without a properly secured scene, crucial evidence can be destroyed, altered, or contaminated, inadvertently or otherwise. Think of it as putting a protective bubble around a delicate ecosystem.

The consequences of mishandling this initial phase are profound. A footprint erased by a curious bystander, a weapon moved by a well-meaning but untrained individual, or a piece of trace evidence blown away by the wind because the area wasn't properly contained – these seemingly small incidents can create insurmountable hurdles for investigators. It's why the training for first responders emphasizes extreme caution and awareness, turning them into temporary custodians of a potential crime’s most critical witness: the scene itself.

Securing the Sanctuary of Evidence: Establishing the Crime Scene Perimeter

Once immediate life-saving actions are underway, the focus shifts entirely to safeguarding the integrity of the scene. This isn't just about keeping people out; it's about controlling a complex environment to ensure that every potential piece of evidence remains undisturbed.

Defining the Boundaries:

The first responder will establish an initial perimeter, often with brightly colored crime scene tape. This isn't a one-size-fits-all approach. The size and scope of the perimeter depend on:

- The Nature of the Crime: A simple burglary might require a smaller perimeter than a homicide with potential projectile paths or a wider area for trace evidence.

- Potential Escape/Entry Routes: Investigators consider how a perpetrator might have entered or exited the scene.

- Witness Locations: Areas where witnesses might have stood or observed are often included.

- Suspect Actions: Did they drop something while fleeing? Did they discard a weapon a block away?

It’s always better to start with a larger perimeter and reduce it later, rather than missing vital evidence by making it too small. This initial zone prevents unauthorized personnel from entering, minimizing disturbance.

Controlling Access and Logging Entrants:

A crucial element of scene security is strictly controlling who enters and exits. A dedicated officer is often assigned to a crime scene log. Every individual, from fellow officers to paramedics, fire department personnel, supervisors, and eventually, forensic specialists, must sign in and out. This log records: - Name and Affiliation: Who is this person?

- Time of Entry and Exit: When did they enter and leave?

- Reason for Entry: Why are they there?

This meticulous record-keeping is vital for establishing the chain of custody later, ensuring that if a piece of evidence is challenged in court, its integrity can be verified. It answers the crucial question: "Who was where, and when?"

Think of a bustling street after an incident, like the initial moments described in the Maple Drive murder case. Without a clear, controlled perimeter and a meticulous log, the potential for vital clues to be trampled or inadvertently moved skyrockets.

Painting a Picture: Documenting the Crime Scene

Once secured, the crime scene becomes an intricate puzzle, and the first step to solving it is to capture its exact state before anything is touched or removed. This process of documentation is paramount, creating an objective, permanent record that can be revisited repeatedly throughout the investigation and presented in court.

The Power of Comprehensive Photography:

Photographs are the eyes of the court and the memory of the investigation. Crime scene photographers take a systematic approach:

- Overall Shots: These wide-angle photos capture the entire scene from various angles, showing its general layout, surrounding areas, and relationship to other structures or landmarks. They establish context.

- Mid-Range Shots: As the photographer moves closer, these shots focus on specific areas or objects within the scene, showing their relationship to other items and their approximate position. For example, a mid-range shot might show a knife on the floor in relation to a doorway or a piece of furniture.

- Close-Up Shots: These are highly detailed photographs of individual items of evidence, taken with a scale (like a ruler) for size reference. These shots capture minute details like serial numbers on a weapon, specific blood spatter patterns, or unique characteristics of a footprint. They are often taken both with and without the scale.

The goal isn't just to take pictures; it's to tell a story through images, ensuring every angle and detail is covered before the scene begins to change.

Detailed Note-Taking: Capturing the Nuances:

Photography provides the visual, but notes provide the narrative. Investigators compile detailed, contemporaneous notes covering: - Date and Time: Every observation is timestamped.

- Weather Conditions: Temperature, humidity, wind, and precipitation can affect evidence.

- Environmental Factors: Lighting, odors, disturbances, open windows/doors.

- Observations of the Scene: The position of objects, their condition, any visible damage, and specific measurements.

- Actions Taken: Who did what, when, and why.

These notes are often written on scene, ensuring accuracy and preventing memory distortion. They serve as a textual map, augmenting the visual information.

Sketches and Diagrams: Spatial Relationships:

While photos capture reality, sketches simplify it, focusing on spatial relationships and measurements that photos sometimes obscure. Crime scene sketches come in various forms: - Rough Sketch: A quick, hand-drawn diagram done on-scene, showing the general layout, dimensions, and approximate positions of evidence. It's not to scale but includes measurements.

- Finished Sketch/Diagram: A more precise, often computer-generated drawing created later, based on the rough sketch and detailed measurements. It's drawn to scale and includes a legend, compass direction, and all pertinent information.

Sketches are invaluable for recreating the scene, especially when discussing distances between objects, entry/exit points, or the trajectory of projectiles. They help visualize the "where" and "how" of the crime.

Together, these three documentation methods — photography, notes, and sketches — form an ironclad record of the crime scene's initial state, a crucial foundation for all subsequent investigative steps.

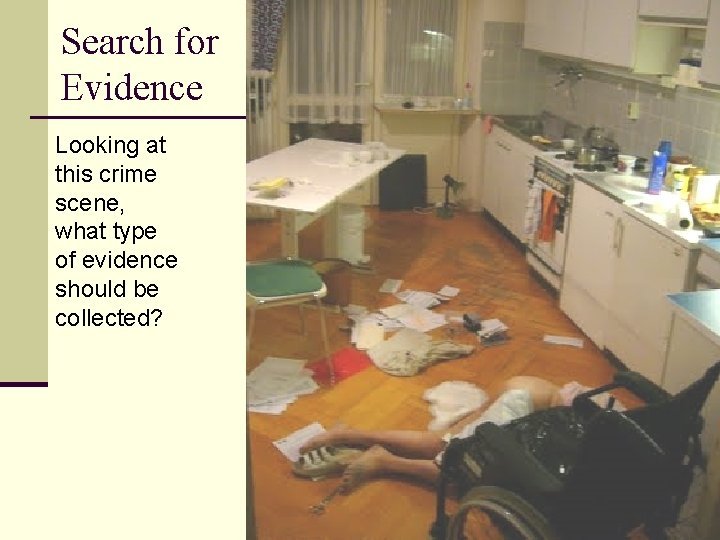

The Forensic Hunt Begins: Systematic Evidence Collection

With the scene secured and thoroughly documented, the meticulous process of collecting physical evidence can begin. This isn't a random treasure hunt; it's a systematic, painstaking search guided by scientific principles and trained observation. The goal is to identify, collect, and preserve every piece of potential evidence, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant.

What Are Investigators Looking For?

The types of evidence can vary wildly depending on the crime, but common categories include:

- Biological Evidence: Blood, semen, saliva, hair, skin cells (source of DNA).

- Impression Evidence: Fingerprints, shoeprints, tire tracks, tool marks.

- Firearms & Ballistics: Weapons, spent casings, projectiles.

- Trace Evidence: Fibers, paint chips, glass fragments, soil, accelerants.

- Documents: Notes, letters, electronic records.

- Digital Evidence: Computers, phones, external drives, surveillance footage.

- Drugs & Controlled Substances: Paraphernalia, residue.

Systematic Search Patterns:

To ensure no area is missed, investigators employ various search patterns: - Spiral Search: Begins at the center and spirals outward (or vice versa), often used for outdoor scenes or when only one investigator is available.

- Grid Search: Two parallel line searches are conducted perpendicular to each other, ensuring thorough coverage, especially for large areas.

- Strip/Line Search: Investigators form a line and walk in parallel paths across the scene, good for large outdoor areas.

- Zone Search: The scene is divided into smaller zones or sectors, and each zone is searched thoroughly by a different team member. Ideal for complex indoor scenes (e.g., house rooms).

The choice of pattern depends on the size and nature of the scene, and the number of personnel available.

Tools of the Trade:

Forensic technicians arrive equipped with specialized tools: - Gloves and PPE: To prevent contamination.

- Tweezers and Forceps: For delicate collection of trace evidence like hairs or fibers.

- Swabs: For collecting biological fluids (blood, saliva, semen).

- Magnifying Glasses and Alternate Light Sources (ALS): To locate subtle evidence like fibers, latent fingerprints, or biological fluids invisible to the naked eye.

- Fingerprint Dusting Kits: Powders and brushes to reveal latent prints.

- Evidence Collection Kits: Pre-packaged supplies for various types of evidence.

- Measuring Tapes and Rulers: For precise documentation.

The meticulousness here is crucial. Every fiber, every drop, every impression holds a piece of the story. For instance, understanding how DNA analysis works highlights why even microscopic biological samples are so critical to collect accurately. It’s an exercise in patience and precision, turning a chaotic scene into a carefully curated collection of clues.

Preserving the Story: Packaging and Labeling Evidence

Collecting evidence is only half the battle; preserving it correctly is equally vital. Improper handling, packaging, or labeling can render even the most compelling piece of evidence useless in court. The goal is to prevent contamination, degradation, and alteration, maintaining the evidence's integrity from the moment it's collected until it's presented in a courtroom.

Appropriate Containers for Different Evidence Types:

- Biological Evidence (blood, semen, tissue): Must be dried thoroughly before packaging to prevent mold and bacterial growth, then placed in breathable containers like paper bags, cardboard boxes, or sealed breathable evidence envelopes. Plastic containers should generally be avoided for wet biologicals as they trap moisture.

- Arson Evidence (accelerants): Placed in airtight, non-reactive containers like new, unpainted metal cans with tight-fitting lids or special arson evidence bags to prevent evaporation.

- Firearms and Ammunition: Securely packaged in sturdy cardboard boxes, often with zip-ties or specialized inserts to prevent movement and accidental discharge.

- Tool Marks and Impression Evidence: Casts are made (e.g., dental stone for footprints), then carefully packaged in boxes. Original items bearing tool marks are collected whenever possible.

- Trace Evidence (hairs, fibers, glass): Often collected using tape lifts, tweezers, or placed in bindles (folded paper packets), then sealed in small, labeled envelopes or plastic containers.

- Digital Devices (phones, computers): Placed in anti-static bags or faraday bags to prevent remote wiping or alteration, and then secured in sturdy boxes. This is particularly important when collecting digital evidence.

Tamper-Evident Seals:

Once packaged, every evidence container is sealed with tamper-evident tape. This tape is specifically designed to show if the package has been opened or compromised after initial sealing. The investigator's initials and the date are typically written across the seal, forming a continuous line across the tape and the container itself.

Detailed Labeling Protocols:

Each package must be meticulously labeled with critical information: - Case Number: Unique identifier for the investigation.

- Item Number: Sequential number for each piece of evidence.

- Description of Evidence: Clear, concise detail (e.g., "red fibrous material," "Colt .45 handgun, serial #12345").

- Location Found: Specific details (e.g., "north wall, 3 ft from window, 2 ft from floor").

- Date and Time of Collection: Exact timestamp.

- Collector's Initials/Badge Number: Identifies who collected it.

Establishing the Chain of Custody:

Beyond packaging and labeling, a meticulously documented Chain of Custody is paramount. This is a chronological record of every person who has come into possession of an item of evidence, from its collection at the scene to its presentation in court.

A typical chain of custody form will record: - Item Description

- Collection Date/Time

- Collector's Name

- Transfer Dates/Times

- Receiver's Name

- Reason for Transfer (e.g., "to lab for analysis," "to evidence locker")

This unbroken record is essential. If a link in the chain is missing or unaccounted for, the defense can argue that the evidence may have been tampered with or compromised, potentially leading to its inadmissibility in court. This is why understanding the chain of custody is so crucial for every person involved in the criminal justice system. It safeguards the integrity of the evidence, ensuring its authenticity and reliability.

Beyond the Tape: Classifying Crime Scenes for a Deeper Dive

Crime scenes aren't monolithic. Each one presents unique challenges and requires tailored investigative strategies. Forensic science classifies scenes in several ways, helping investigators organize their approach and anticipate the types of evidence they might find.

By Location:

- Primary Scene: This is where the initial criminal act occurred. For example, in a homicide, it's the location where the victim was attacked. This scene often holds the most direct evidence related to the core event.

- Secondary/Tertiary Scenes: These are related locations where subsequent events or evidence might be found. A secondary scene could be where a body was dumped after a murder committed elsewhere, or where a weapon was discarded. These scenes are crucial as they often provide links between the primary event and other related actions of the perpetrator.

By Visibility/Scale: - Macroscopic Scene: These are the large-scale, visible elements of the crime scene that you can observe with the naked eye. This includes the general layout of a room, a body, a weapon, furniture displacement, or large bloodstains. A macroscopic scene often encompasses several individual "investigation levels," like a bank robbery scene including the entry point, the teller counter, and the vault.

- Microscopic Scene: This classification deals with the tiny, often invisible-to-the-naked-eye trace evidence. This includes hairs, fibers, DNA, soil, glass fragments, paint chips, and pollen. Microscopic scenes require specialized tools like magnifiers, alternate light sources, and laboratory analysis to detect and identify. It highlights the principle that even the smallest fragment can tell a significant story.

By Crime Type:

The nature of the crime directly influences the type of evidence investigators expect to find and the methods they employ. - Homicide: Investigators focus on blood spatter, weapons, DNA, and signs of struggle.

- Sexual Assault: Emphasis on biological evidence, torn clothing, and trace evidence transfer.

- Burglary/Robbery: Focus on forced entry points, tool marks, fingerprints, and items taken or left behind.

- Arson: Search for accelerants, ignition points, and fire patterns.

Each crime type dictates specific protocols and forensic specialties needed.

By Criminal Behavior/Modus Operandi (MO):

Beyond classifying the scene itself, investigators also categorize scenes by the perpetrator's behavior. The "modus operandi" refers to the specific methods or characteristics a criminal uses consistently. This helps to: - Link Cases: If multiple crimes share a distinct MO (e.g., a specific method of entry, type of victim, or signature act), they might be linked to the same perpetrator.

- Profile Suspects: The MO can provide insights into the perpetrator's personality, planning, and habits, aiding in suspect identification.

Understanding these classifications allows investigators to adopt a more focused and effective approach, ensuring that no potential avenue for evidence or insight is overlooked.

The Mind Behind the Method: Investigative Approaches

Solving a crime isn't always a straightforward, linear path. Investigators often employ different thought processes and methodologies to piece together the events, moving between systematic examination and intuitive inference.

Linear Progression: The Systematic Search

This approach is highly structured and methodical, primarily driven by crime scene technicians and forensic specialists. It involves a step-by-step process designed to ensure no evidence is overlooked and that all findings are meticulously documented.

- Recognition: This is the initial scene survey, where investigators observe, identify potential evidence, and begin creating a mental map. It's followed by comprehensive documentation through narrative reports, diagrams, sketches, and photographs.

- Identification: Here, potential evidence is carefully separated from irrelevant items. Chemical, biological, and physical tests may be used on-scene or shortly after to confirm the nature of a substance (e.g., presumptive blood tests).

- Collection and Preservation: As discussed, this involves using specific methods for each evidence type to protect it from contamination or degradation, preparing it for transport to the lab.

- Individualization: In the lab, evidence is analyzed to connect it to a specific source. For example, matching a fingerprint to a person, a bullet to a specific firearm, or DNA to an individual. This step helps establish the "who" and "what" definitively.

The linear approach is the backbone of forensic science, providing objective, verifiable data.

Nonlinear Progression: Pattern Recognition and Inference

While the linear approach provides the scientific foundation, investigation also involves a significant degree of nonlinear thinking, often employed by detectives and lead investigators. This is a more dynamic process, focusing on patterns, inferences, and logical deductions.

- Less Systematic, More Intuitive: Rather than a strict sequence, nonlinear progression involves a continuous loop of observation, hypothesis, and testing. Investigators might draw connections between disparate pieces of information, forming theories about how the crime occurred.

- Reasonable Inference: Based on experience and understanding of criminal behavior, investigators make educated guesses or inferences about the events. For example, if a door is kicked in, they infer forced entry. If specific items are missing, they infer theft.

- Dynamic Process: As new information emerges, hypotheses are refined or discarded. This iterative process helps to build a comprehensive picture of the criminal act, focusing not just on what happened, but also on the "why" and "how."

- Corroboration: The inferences drawn from nonlinear thinking are then rigorously tested against the physical evidence identified through linear progression. Physical evidence either corroborates or refutes these theories, helping to reconstruct the crime.

Both linear and nonlinear approaches are crucial. The systematic collection of physical evidence (linear) provides the objective facts, while the interpretive, pattern-seeking nature of nonlinear thinking helps to contextualize those facts and build a compelling narrative of the crime.

The Lab's Unseen Work: Unlocking Evidence's Secrets

The crime scene investigation isn't over when the tape comes down and the evidence is transported. In many ways, the real work of uncovering truth begins in the sterile, high-tech environment of the forensic laboratory. Here, forensic scientists, armed with advanced tools and specialized knowledge, delve into the collected evidence to extract its hidden stories.

Role of Forensic Laboratories:

Forensic labs are hubs of scientific analysis. Their primary purpose is to objectively examine physical evidence using established scientific methods, providing data that can corroborate or refute theories, identify individuals, and inform the legal system. They act as impartial scientific interpreters for the silent witnesses left at the scene.

Examples of Analyses:

- DNA Analysis: Perhaps the most powerful tool in modern forensics, DNA analysis can identify individuals with incredible precision. From a tiny skin cell, a drop of blood, or a strand of hair, scientists can create a genetic profile. This profile can be matched to a suspect, linked to a victim, or entered into national databases like CODIS (Combined DNA Index System) to search for potential matches from other crimes. Understanding how DNA analysis works reveals the meticulous steps involved, from extraction to amplification and profiling.

- Fingerprint Comparison: Latent (invisible) fingerprints, lifted from a crime scene, are processed and compared to known prints of suspects or entered into AFIS (Automated Fingerprint Identification System) databases. Every ridge, loop, and whorl tells a unique story.

- Ballistics Analysis: When a firearm is involved, ballistics experts examine bullets and spent casings. They can determine the type of weapon used, and often, through microscopic comparison of unique striations, match a specific bullet or casing to a specific firearm. This analysis can directly link a weapon to a crime.

- Toxicology: In cases involving drugs, alcohol, or poisons, toxicologists analyze biological samples (blood, urine, tissue) to identify and quantify substances, providing crucial information about a victim's or perpetrator's state.

- Trace Evidence Analysis: Experts analyze minute fragments like fibers, paint chips, glass, soil, or explosive residues. For example, comparing a fiber found on a victim to fibers from a suspect's clothing can establish a direct link.

- Digital Forensics: With the rise of technology, digital evidence has become paramount. Digital forensic specialists extract data from computers, smartphones, tablets, and other electronic devices. This can include call logs, text messages, emails, browsing history, GPS data, and even deleted files, all crucial for reconstructing events or establishing alibis. The methods for collecting digital evidence are highly specialized to prevent data corruption.

- Forensic Pathology: While medical examiners primarily work at the scene and during autopsy, their findings are analyzed and interpreted in a scientific context to determine the cause and manner of death.

The laboratory transforms raw evidence into actionable intelligence. It provides the objective, science-based data that underpins criminal investigations, offering tangible proof that stands up to scrutiny in the legal system.

Who's Who at the Scene: Key Players in the Investigation

A successful crime scene investigation is never a solo act. It's a complex collaboration involving a diverse team of professionals, each bringing specialized skills and expertise. Understanding their roles helps clarify the intricate dance that unfolds from initial discovery to final resolution.

- First Responders (Law Enforcement Officers): These are the initial uniformed officers (e.g., patrol officers, deputies) who arrive at the scene. Their responsibilities are critical:

- Emergency Aid: Provide immediate assistance to victims and ensure safety.

- Securing the Scene: Establish a perimeter, control access, and prevent contamination.

- Initial Observations: Document the scene's initial state, witness statements, and any immediate facts. They are the eyes and ears until specialized units arrive.

- Crime Scene Technicians (CSTs) / Forensic Specialists: These highly trained individuals are the backbone of evidence collection. They are experts in the scientific process of identifying, documenting, collecting, and preserving physical evidence.

- Systematic Search: Conduct thorough, patterned searches for all types of evidence.

- Documentation: Execute detailed photography, sketching, and note-taking.

- Evidence Collection: Use appropriate tools and techniques to collect, package, and label evidence while maintaining the chain of custody.

- Specialized Expertise: Some may specialize in fingerprints, DNA, ballistics, or digital forensics.

- Detectives and Investigators: These experienced law enforcement personnel lead the overall investigation, guiding the direction based on collected evidence and witness statements.

- Case Management: Oversee the entire investigation, coordinating efforts between various teams.

- Lead Development: Develop theories, identify suspects, and follow up on leads generated by physical evidence and witness interviews.

- Witness Interviews: Conduct in-depth interviews with witnesses and potential suspects. Understanding effective witness interview techniques is crucial for their role.

- Collaboration: Work closely with CSTs, forensic labs, and other agencies.

- Medical Examiners (MEs) / Coroners: In cases involving fatalities, MEs or coroners are crucial. They are physicians (MEs) or elected/appointed officials (coroners) responsible for investigating deaths that are sudden, violent, unexpected, or suspicious.

- On-Scene Assessment: Examine the deceased at the crime scene to gather initial observations about the body's position, injuries, and surroundings.

- Autopsy: Conduct a post-mortem examination to determine the cause and manner of death, collect forensic samples (e.g., toxicology, DNA), and provide expert testimony.

- Time of Death: Provide crucial estimates on the time of death, which helps in narrowing down suspect timelines.

Beyond these core players, other specialists like K9 units, anthropologists, odontologists (dentists), and digital forensic experts may be called upon depending on the specific needs of the scene. Each plays a vital role in reconstructing the events and bringing clarity to the unknown.

Modern Forensics: A Glimpse into Tomorrow's Crime Solving

The landscape of crime scene investigation has undergone a revolutionary transformation, especially since the mid-20th century. What was once largely reliant on intuition and basic observation is now a sophisticated interplay of cutting-edge science and technology.

Technological Advancements:

- Automated DNA and Fingerprint Systems: The days of manually comparing thousands of fingerprints are largely over. AFIS (Automated Fingerprint Identification System) and CODIS (Combined DNA Index System) allow for rapid cross-referencing of prints and genetic profiles against vast databases, significantly speeding up suspect identification and linking cold cases.

- Enhanced Trace Evidence Detection: New technologies allow for the detection and analysis of even smaller, more degraded trace evidence. Advanced microscopes, spectroscopy (analyzing light interactions with matter), and chemical profiling techniques can extract information from the tiniest fibers, paint chips, or residues.

- Advanced Imaging and 3D Scanning: High-resolution digital photography, drone footage, and 3D laser scanners create incredibly accurate, immersive digital models of crime scenes. These models can be virtually "revisited" by investigators, allowing for precise measurements, trajectory analysis, and even virtual walkthroughs long after the physical scene has been released.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI is beginning to assist in various aspects, from analyzing vast amounts of data (like surveillance footage or digital communications) to identifying patterns in criminal behavior, predicting crime hotspots, and even aiding in facial recognition.

- Virtual Reality (VR) Reconstruction: VR technology allows investigators, prosecutors, and even jurors to experience a crime scene almost as if they were there, providing a deeper understanding of spatial relationships and events.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): This advanced DNA sequencing technology can analyze highly degraded or mixed DNA samples, pushing the boundaries of what's possible with genetic evidence.

Improved Interagency Cooperation:

As criminal activity becomes more complex and often crosses jurisdictional lines, the need for seamless cooperation between local, state, and federal agencies has never been greater. Shared databases, standardized protocols, and joint task forces ensure that information and resources are efficiently pooled, leading to more comprehensive investigations and a higher clearance rate for crimes.

These advancements don't just make investigations more efficient; they make them more accurate, reliable, and capable of solving cases that would have been impossible just a few decades ago.

Navigating the "CSI Effect": Realism vs. Expectation

Modern crime shows, with their dramatic reveals and rapid forensic results, have captivated audiences worldwide. While these shows introduce the public to the fascinating world of forensic science, they've also inadvertently created what's known as the "CSI Effect."

The Misconception:

The "CSI Effect" refers to the phenomenon where jurors, influenced by fictional portrayals, develop unrealistic expectations about forensic evidence in real-life criminal trials. They might expect:

- Abundant Forensic Evidence: That every crime scene will yield pristine DNA, perfect fingerprints, and a conclusive scientific answer.

- Instant Results: That lab tests can be completed in hours, not weeks or months.

- Omnipresent Technology: That advanced forensic techniques, like highly specialized trace analysis or elaborate 3D reconstructions, are standard practice in every case, regardless of budget or resources.

- Infallible Science: That forensic science is always 100% conclusive and never involves interpretation or limitations.

The Reality:

In the real world, crime scenes are often messy, degraded, and yield sparse or ambiguous evidence. Trace evidence might be minute, fingerprints smudged, and DNA samples contaminated. Lab results take time due to backlogs and the meticulous nature of the analysis. Furthermore, not every police department has access to the most advanced technologies, and even the most sophisticated science has its limitations.

The Impact on Investigations and Trials:

The "CSI Effect" presents several challenges: - Increased Juror Scrutiny: Jurors may demand more forensic evidence than is realistically available for a conviction, even when strong testimonial or circumstantial evidence exists.

- Defense Strategy: Defense attorneys often exploit these expectations by highlighting the absence of certain forensic evidence, even if its presence wouldn't be expected.

- Investigator Burden: It places pressure on investigators and prosecutors to meticulously explain standard operating procedures, limitations of forensic science, and why certain evidence might not be present or conclusive.

To counter this, law enforcement and legal professionals must: - Educate Jurors: Clearly explain the realities of crime scene investigation and forensic science.

- Adhere to SOPs: Meticulously follow standard operating procedures to ensure evidence is collected and analyzed reliably, making it less vulnerable to challenge.

- Focus on Evidence-Based Storytelling: Present the available evidence clearly, explaining what it can and cannot tell the court, rather than relying on fictionalized expectations.

The "CSI Effect" underscores the importance of public education and emphasizes that real justice is built on careful, painstaking work, not on Hollywood timelines or perfect outcomes.

Your Role in the Aftermath: What to Do if You Discover a Crime Scene

While most of us will never be directly involved in a crime scene investigation, discovering something suspicious or potentially criminal is a terrifying possibility. Knowing what to do in those critical first moments can protect yourself and ensure vital evidence is preserved.

1. Safety First, Always:

Your personal safety is the absolute priority. If you believe a crime is still in progress, or if there's any immediate danger (e.g., an armed suspect, a fire, hazardous materials), remove yourself from the situation immediately. Do not approach or confront anyone.

2. Do NOT Touch, Alter, or Move Anything:

This is the single most important rule regarding potential evidence. Resist the urge to "help," clean up, or even just curiously poke around.

- Don't touch the victim (unless rendering emergency aid is absolutely necessary): If you must provide first aid, try to disturb as little as possible.

- Don't pick up objects: A weapon, a piece of paper, or any other item could have crucial fingerprints, DNA, or trace evidence.

- Don't clean anything: Blood, dirt, or other substances might be critical evidence.

- Don't open or close doors/windows: These could have prints or show entry/exit points.

- Don't use the phone/toilet/sink: These are potential sources of DNA and fingerprints.

- Don't walk through the area unnecessarily: Every step can destroy microscopic evidence like fibers or footprints.

3. Call Authorities Immediately:

As soon as you are safe, call 911 (or your local emergency number). - Provide a Clear Location: Be as specific as possible (street address, landmarks, cross streets).

- Briefly Describe What You've Found: State the nature of the discovery without speculation.

- Answer Their Questions: Follow their instructions carefully.

4. Observe and Remember (Without Entering/Touching):

From a safe distance, try to observe and recall details that might be helpful to responding officers: - Any people or vehicles leaving the scene? Descriptions, direction of travel.

- Unusual sounds or smells? (e.g., gunshots, breaking glass, chemical odors).

- Time of discovery.

- Any disturbances in the area?

5. Stay on Scene (If Safe) Until Authorities Arrive:

If it is safe to do so, remain at a safe distance to direct emergency personnel and provide them with your observations. Your presence and clear communication can save precious minutes.

By following these guidelines, you become an invaluable part of the initial response, helping to preserve the integrity of a potential crime scene and aiding law enforcement in their critical task.

The Unfolding Narrative: From Discovery to Justice

The initial discovery of a crime scene is far more than a moment of shock or tragedy; it's the genesis of a meticulously constructed narrative. From the first responder's swift actions to secure the area, through the diligent documentation, the systematic collection of microscopic clues, and the rigorous scientific analysis in the lab, every step is a chapter in the unfolding story of what happened.

This intricate process isn't just about collecting facts; it's about giving voice to the voiceless, revealing truths hidden in plain sight, and ensuring that justice, informed by objective evidence, can ultimately prevail. The sanctity of the crime scene and the precision of its initial handling are the bedrock upon which trust in the legal system is built. It’s a testament to human ingenuity and dedication that, from a scene of chaos, order and truth can be meticulously brought to light.